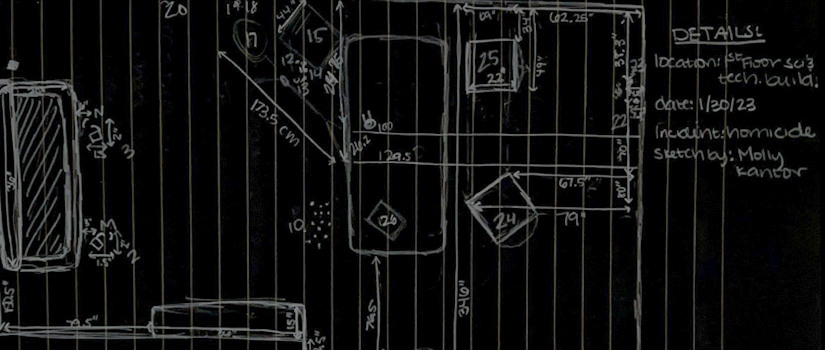

On the first day of her forensic chemistry lab, Molly Kantor walked into a room cordoned off with yellow crime scene tape. She stepped carefully to avoid the broken glass that littered the floor. A storage container with a broken lock sat in the corner.

“We saw the casing from a spent bullet, and there was a fake body with blood spatter on the wall and floor nearby,” Kantor says.

Students took pictures and noted measurements for everything they saw in the fictional crime scene, trying to find clues for what may have happened.

“I felt like I was putting together a puzzle,” says Kantor, a freshman anthropology major at the University of South Carolina.

Kantor aspires to work for the FBI as a forensic scientist. Throughout the semester, Kantor and her classmates learned about the techniques needed to analyze the evidence found in crime scenes.

Bringing relief to the families and those affected is my reason behind doing this for my future career. I want to try to help in some way.

Molly Kantor, freshman

The forensic chemistry class, taught by Dr. Way Fountain of the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, is part of a new forensics minor. Kantor is one of the first in the new program, which will help USC students meet a need for forensic scientists in South Carolina.

“There are several active forensics labs in the state, in addition to those that hire contractors,” Fountain says. “One of the challenges for these agencies is that they have to recruit from out of state.”

Fountain has been working with the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division and other agencies to develop courses to equip students with skills for forensics jobs. After a long career as one of the most senior chemists with the U.S. Army, Fountain has a passion for forensics and the expertise to bring the program to fruition.

Fountain was a professor at West Point before serving as a senior research scientist for the Pentagon and the Aberdeen Proving Ground, where he started the Army’s counter-IED forensics program. He worked to identify explosives and use the evidence to help determine who was behind bombings during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Now, Fountain is working with the College of Arts and Sciences to develop the forensics minor into an interdisciplinary major, which could then be certified by the Forensic Science Education Programs Accreditation Commission.

For the time being, students who complete the minor will have skills to meet some of the staffing needs in the state, and Fountain is hopeful that the new program will attract more students to the field.

“This program is an opportunity for students to learn about forensic science and make decisions on whether this is the type of career they want to pursue,” Fountain says.

Forensics as a way of life

Kantor says coupling the forensics minor with her anthropology major will position her well to specialize in forensic anthropology in pursuit of her dream of working for the FBI.

Kantor will be in good hands with a slate of courses offered by faculty across departments and programs at the college, including criminal justice, sociology, philosophy, anthropology and the physical sciences.

As part of the minor, she’ll study human remains identification, ethics and homicide analysis, topics she says have always interested her.

“I know it sounds strange to say, but I’ve always been interested in studying bones,” she says.

While she acknowledges that studying forensics can get into darker areas of human experience, Kantor says she stays grounded by knowing that the work ultimately brings justice to these situations.

“This is my way of life – bringing relief to the families and those affected is my reason behind doing this for my future career. I want to try to help in some way,” she says.

In the lab class, Kantor saw how intensive the work is, looking at the fine details of bullet casings, hair samples and fingerprints.

While TV shows and movies about forensic work often show analysts coming up with instant answers and a perfect match in a convenient database, the science is more complicated.

Fingerprints, for example, rarely if ever line up perfectly. A forensic analyst finds similarities between a sample and the partial, imperfect prints found at a crime scene to make the case.

“On a TV show, you see them solve a crime in about 45 minutes, when in reality, it all takes so much longer,” Kantor says.

“I have a lot of respect for people who are in this line of work, because it’s certainly not easy.”

Are you interested in forensics?

Students in any major can take the forensics minor, but a background in physical science is recommended to pursue a career in the field. The minor pairs well with majors in anthropology, biology, chemistry and biochemistry, criminal justice, neuroscience, psychology and others.

Do you want to explore the field in a class or two?

Some forensics courses offered may meet requirements for physical science and social science degrees, such as philosophy and sociology. Learn more in the undergraduate bulletin.